This Report is intended for use by global companies seeking information on sustainability strategies that deliver business value – economic, social, and environmental performance improvement. It was prepared by Susan Graff and a team of researchers for presentation at The Conference Board: The Promise and Challenge of Sustainable Development conference held in New York June 14, 2005.

Introduction

In the context of an ever-changing, globally connected society, businesses face new and different risks in providing goods and services. A new trend for multi-national corporations is to establish corporate sustainability business practices to address these risks, and at the same time discover new growth opportunities.

This benchmark report presents the common elements of strategy among high performing companies, along with case examples and the business value they reported from these efforts.

This report is based on a 2004 benchmarking project of 28 global companies sponsored by a Fortune 60 manufacturing client partner. From this group, the research team held personal interviews with senior managers from nine companies that had the highest combined scores on sustainability indices, reputation polls, and corporate sustainability core competencies linked to shareholder value. The companies were initially screened on global sustainability and reputation indices as well as participation in the World Business Council for Sustainable Development. The sustainability indices included leadership in the Dow Jones Sustainability World and FTSE4Good. Reputation polls included Fortune’s list of the World’s Most Admired Companies, Financial Times list of the World’s Most Respected Companies, and The Harris Reputation Quotient. The companies were secondarily screened using the Sustainability Scorecard®, an analytic tool that rates performance on five corporate sustainability competencies associated with shareholder return. From the scorecard results, nine companies were selected for interviews. The companies represented a diverse mix of industries, including finance, manufacturing, construction, extractive, and industrial transportation headquartered in the U.S., Europe, and Asia.

The Sustainability Scorecard® methodology is based on numerous research studies over the past 15 years that show a positive association between corporate sustainability competencies and shareholder value. The Scorecard treats shareholder return as the financial measure affected by significant intangibles such as corporate reputation, competitive position, employee engagement, innovation, and ability to mitigate risk. It assesses five major organizational competencies demonstrated by companies with superior shareholder return, as measured by percent change in stock price over a 10-year period. The Scorecard competencies include, but are not limited to, transparent reporting of results to stakeholders, innovation “beyond compliance” and consideration of sustainability impacts throughout the life cycle.

Based on the Scorecard results, the research team identified nine companies that had the highest combined scores on sustainability indices, reputation polls, and corporate sustainability core competencies. Personal interviews were conducted with VPs and senior managers from the nine companies, and the following section contains the highlights of our analysis.

The Business Value of a Corporate Sustainability Strategy

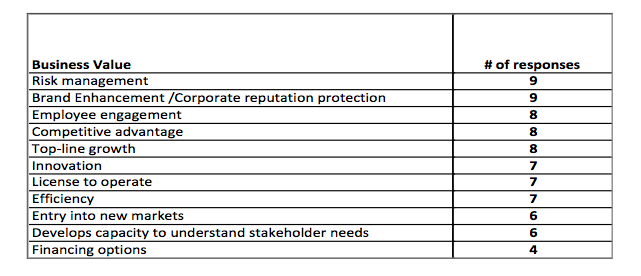

The companies we interviewed consistently reported risk management, brand enhancement, and protection of corporate reputation as the business value gained from a deliberate focus on corporate sustainability. The following chart provides a summary ranking of all responses.

What is the Business Value of a Corporate Sustainability Strategy?

The Eight Common Elements of Successful Corporate Sustainability Strategies

Common elements emerged that were essential to developing corporate sustainability priorities for these companies. All eight elements contribute to development of business practices that objectively identify risk and pursuit of new business growth opportunities.

1. Engagement with NGOs and Other Stakeholders as Advisors

All but one company interviewed stressed the benefits of engaging with stakeholders, and the one company that was not engaging stakeholders was tracking major stakeholder activities and considering them internally. The benefits of stakeholder engagement were consistently reported as learning of potential risks and managing them proactively before they reach a crisis point. Developing the organizational capacity to engage stakeholders and evaluate this input in terms of company risk is essential to a successful corporate sustainability program. Stakeholder engagement keeps a company in touch with the rapidly evolving world of environmental and social risks and opportunities. Without this ability to understand and respond to risks and opportunities as they develop, companies are left to deal with crises and the difficulties of catching up to their competitors.

Citigroup believes so firmly in engaging stakeholders that they “make a real effort to talk to external stakeholders, even those who are critical of us and we learn from these interactions.” Pamela Flaherty, Citigroup’s Senior Vice President specifically warned of the complacency from only listening to voices from inside the company that repeat the “party line.” “It is so easy to listen to yourself [and think you know what is really going on],” she says. Citigroup listed the following benefits from stakeholder engagement:

- Gain intelligence on emerging trends – both risks and opportunities

- Allows company to resolve perceived issues they may be unaware of before issue becomes a crisis

- Gain external perspective on company reputation

- Learn of specific company projects that are not receiving recognition

- Manage risk from stakeholder groups by establishing communication pathways

UPS engaged two non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the World Resources Institute and Business for Social Responsibility, when developing their corporate sustainability program and echoed Citigroup’s sentiments. These NGOs helped raise the Company’s awareness that they were perceived as having unfair labor practices, because of their reliance on part-time workers. The reality was their workers were treated very well and given benefits. UPS was able to proactively address the perceived labor issue through independent party identification of business risk.

2. Corporate Sustainability Program Designed Around Risks

All of the companies benchmarked emphasized the centrality of risk management to corporate sustainability. Corporate sustainability has its roots in the proactive management of risk. This is the greatest value of corporate sustainability and also the most difficult to measure. The basis of the corporate sustainability programs of each company interviewed essentially involved identifying priority risks and then developing a principled and clear response to those risks. Sometimes these risks were manifested by NGO and media exposure, which resulted in a crisis. For most of the companies interviewed, there was recognition of emerging risks presenting potential crisis.

At 3M, management took quick action when disclosures mandated by the pending “Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act” in 1986 indicated they may be one of the largest emitters of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the Midwest. This position presented an unacceptable risk. They set about making process changes to reduce their emissions and succeeded in doing so by over ninety percent. They have also addressed product-related issues before there was a crisis, including solvent-based tapes and adhesives, because they felt it presented unacceptable business risk.

For Citigroup, extensive stakeholder engagement revealed a growing concern of their role in financing projects that have significant negative ecological and social impacts. Understanding this as an important risk, Citigroup responded proactively by spearheading the development of the Equator Principles with 18 other financial institutions. The Equator Principles mandate projects above $50 million satisfy significant environmental and social criteria. Citigroup transformed this risk into an opportunity to demonstrate leadership to their stakeholders and enhance the value of their brand.

In the case of Nike, the company originally focused their efforts on designing eco-efficient products. This focus grew out of employee interests, rather than risk management. Nike had not considered their contractors work practices as a major risk. A crisis emerged when certain stakeholders considered them responsible for the behavior of their contractors. Since then labor issues have become a focus area where the company is very responsive. They have engaged with international labor organizations to create standards and auditing systems to ensure humane working conditions.

3. Focus on Corporate Sustainability Risks Creates Business Opportunities

3M is a good example of a company where business opportunities have emerged through insights generated from risk management initiatives. 3M developed an extensive life cycle management process for evaluating the environmental, safety, and health impacts of their products. They have become extremely adept at refining processes, reformulating products, and taking other actions to reduce impacts. Now they are using this competency to solve problems for their customers. An example is a furniture company that faced environmental issues because of a VOC in the glue used in their production process. In response, 3M developed glue with the same functional qualities, but without the VOC. As a result, the furniture company was able to avoid the installation of extremely expensive pollution control equipment.

Procter and Gamble focused their early corporate sustainability efforts at eco-efficiency and while they reaped significant bottom-line cost savings from these efforts, grew dissatisfied because they failed to reap any top-line benefit. They have since refocused their efforts on creating products that provide health, environmental and social benefits to the “bottom of the pyramid” customers. Skills and processes the company developed from their risk management initiatives – skill in working effectively with NGOs and the focus on environmentally and socially responsive design innovation – now yield opportunities for the development of new markets.

4. Culture Aligned with Social Responsibility

Most of the companies interviewed had a culture closely aligned with corporate sustainability, which made its integrating corporate sustainability easier. Given that these companies already operated from a culture committed to efficiency, innovation, and responsibility, they may have been the first to recognize the value from integrating corporate sustainability. In any event, all reported their natural affinity with corporate sustainability made its introduction, at least initially, much easier.

Toyota has had a production system predicated on the identification and elimination of inefficiencies and waste since its inception as a company. The culture stresses “Kaizen Consciousness” – a state of awareness to possible improvements – among its workers. For Toyota, the adoption of eco-efficiency in its design and production was simply a natural extension of this point of view.

UPS has a somewhat similar culture in this respect. The company stresses a mindset of “Constructive Dissatisfaction” among employees to keep them in constant vigilance for new and better solutions. As Mike Herr, UPS Vice President Environmental Affairs says, “Our company culture is built on efficiency, so transition to a sustainability perspective was just a natural extension of things we had already been doing. Our sustainability vision takes efficiency and adds a social and environmental perspective to it.”

5. Management Commitment Essential to Success

Even with this set of benchmarked companies – most of which report having a “culture aligned with CSR” – all reported that getting “buy-in” from business groups was the most difficult thing to achieve. This is difficult primarily because business units do not see the financial value of corporate sustainability. Most managers have thoroughly internalized the view that their sole purpose is to improve the value of the company for the company’s shareholders. Corporate sustainability appears to be philanthropy and they do not see how it adds value to the shareholders. The benefits of corporate sustainability are, in many cases, very difficult to measure and so managers do not want to devote resources to initiatives that will not yield a quantifiable return.

In order to get “buy-in” from business groups and to truly integrate corporate sustainability throughout a company’s operations, it was critical the initiative be driven and reinforced from top management. This always involved the CEO in a central role and often extended into the Board of Directors. It was essential all employees understand that corporate sustainability was an element of the company’s strategy which was important for their overall success. Without this clear focus, business units would continue to resist on an issue-by-issue basis, and create conflict where there must be alignment. In order for corporate sustainability to reduce risk to a company’s brand, there must be alignment throughout the company. If one unit of the company is exposed as having unsafe environmental practices, then the company as a whole suffers.

At 3M, there was a long tradition of eco-efficiency and waste reduction initiatives dating back to the mid-seventies. When the current CEO came in, a new product introduction system was developed that integrated sustainable development into the business process through a life cycle management approach. In addition, environmental and social metrics were integrated into EHS performance scorecards for businesses and facilities, which tied directly to individual performance evaluations. By integrating corporate sustainability into performance evaluations, this formalized corporate sustainability as an important business process and acknowledged employee behavior that was tied to performance.

As Ms. Flaherty of Citigroup observes, “The 40,000 foot view is not the way to implement.” Citigroup has found a very innovative way to achieve “buy-in” from its business unit executives – put them in direct contact with stakeholders. When Citigroup learned from stakeholders that it was important for them to integrate social and environmental considerations into their lending practices, the company realized change had to take place in the business groups in charge of financing. The leaders of these groups were initially skeptical and resistant to this kind of change. Ms. Flaherty arranged for moderated opportunities for business group leaders to engage directly with stakeholders. This engagement took place within the context of top management’s strategic commitment to addressing these issues, but the direct engagement helped these group leaders understand the issues and take ownership and responsibility for them. It also allowed them to be regarded as the management champion when these initiatives were implemented and thereby decreased resistance to future initiatives.

The principal lesson here is this: if getting “buy-in” from business units has been difficult in these companies – whose cultures were often “pre-aligned” to corporate sustainability – then it will be doubly so in companies where the culture is more standard. It will require a consistent focus, follow-up, and very clear internal and external communication.

6. Financial Value is Difficult to Measure

The majority of companies interviewed did not make a concerted effort to measure the financial value of their corporate sustainability programs. They generally regarded corporate sustainability as an essential element to having a successful business. While many of the companies interviewed had reaped substantial bottom-line benefits from eco-efficiency and waste reduction, all agreed these were not the most important aspects of business value derived from corporate sustainability.

According to Mike Herr at UPS, corporate sustainability “protects operations locally, it doesn’t make you a target, and it helps you gain access in emerging economies.” It is difficult to put a dollar figure on these advantages. Although Nike is currently working on a system to measure the return on investment from individual projects, Sarah Severn, Nike’s Director of Sustainable Development, states ultimately the real value of corporate sustainability is very difficult to measure. For Nike, the value of corporate sustainability is, “first and foremost, brand enhancement and protection. Being on the cutting edge of integrating corporate sustainability into business signals that Nike is an innovator and is paying close attention to trends. We also see it as a way to foster innovation and drive operational excellence.”

When asked to name the most important advantages of Citigroup’s corporate sustainability program, Ms. Flaherty responded simply and directly, “We think of ourselves as a global leader and so does the world. The advantages of doing well are immeasurable. The downsides are a place you don’t want to go.”

7. The Importance of Independent Auditing and Assurance

Most of the companies interviewed, with the exception of two, were using auditing and independent verification to assure their social and environmental business practices were being carried out in operations as intended.

While Citigroup does not have a third-party audit for social and environment initiatives, internally the company conducts a self-audit assessing compliance with its practices and policies. For one light manufacturer, auditing does not have the same kind of risk management impact it does in a heavy manufacturing or extractive industry context.

Extractive industry firms have the most exhaustive assurance mechanisms for their operations. This is because environmental and social issues can be a crucial determiner of license to operate for the company. These companies must know what is happening on the ground in operations that are spread out across the globe so they can manage effectively.

8. Clear, Detailed, Transparent Reporting

All but one of the companies interviewed stressed the importance of clear, honest and transparent reporting in order to let stakeholders know what the company is doing and to give their efforts credibility. The power of stakeholder groups is increasing and communication pathways, such as the Internet, are making the flow of information instantaneous. These trends are likely to continue to accelerate in the future and multinational corporations will be more and more under the microscope.

When developing UPS’s first sustainability report, Mike Herr states they “realized we needed to codify our corporate sustainability strategy, policies and initiatives and report them to stakeholders. We realized that if UPS did not tell its own story, then eventually someone else was going to tell it for us. We wanted to tell our story transparently so our position would be clear.” UPS was very clear and honest in its report about what data they had and what important data they did not have about their social and environmental performance. They made no claims that could not be supported with data. They pledged to gather the necessary data to report on all identified issues of material concern for their next report.

Toyota has also focused a great deal on reporting on both global and regional operations. Their web site states that if you are under scrutiny, then you must be aware of it and act accordingly. All of this transparency builds trust with stakeholders who gain a more accurate picture of the ways Toyota is addressing risks.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the companies benchmarked embraced the same strategies in their respective corporate sustainability programs despite their differences in industry. Why?

First, every strategy was a means to mitigating risk- particularly risk to the brand and risk to corporate reputation. Furthermore, companies are strengthening internal processes to identify risks with input from their external stakeholders. An expanded definition of risk was validated by the interviews – risk is defined as anything that can cause business disruption in the changing global business environment.

Secondly, though they had different business needs, all companies demanded their corporate sustainability programs create shareholder and customer value. Each strategy is a means to managing risk but also to creating opportunities. The majority of companies report employee engagement, competitive advantage, top-line growth, innovation, license to operate, and efficiency as the business benefits of their corporate sustainability programs.

Finally, every strategy provides data which demonstrates their corporate responsibility to their stakeholders, if not to shareholders. Surprisingly, these companies aren’t measuring the benefits they receive from being a socially responsible company. Instead, they measure, assure and report what they do to be socially responsible – including eco-efficiency, ethics, and human resource development.

The researchers hope this report has provided a broader view from the experience of corporate sustainability practitioners and critical learning to help integrate these best practices into your business. For more information about this study, please contact Susan Graff.

___________________________

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are deeply grateful for the case examples provided by the following benchmark study participants who shared their perspective so that other companies may benefit from their experiences.

3M – Keith Miller, Environmental Initiative & Sustainability Manager

Citigroup – Pamela Flaherty, Sr. Vice President Corporate Citizenship & Environmental Affairs Nike – Sarah Severn, Director of Corporate Sustainable Development Procter & Gamble (P&G) – George Carpenter, Director Corporate Sustainable Development United Parcel Systems (UPS) – Mike Herr, Vice President Environmental Affairs

___________________________

Susan Graff is a sustainability practitioner and expert in environmental management and science policy. This research was performed under her direction at ERS Global, where Susan served as Principal and founder to provide strategic, performance-based sustainability consulting services to Fortune 500 companies. Prior to ERS, Susan was a senior official with US EPA, serving as a change agent and program manager in the areas of risk assessment, materials and waste management, site assessment, and regulatory incentive programs. Her credentials include an MS in Technology and Science Policy from Georgia Tech and a BS in Biology from Western Illinois University. She serves on the Board of Directors at Georgia Tech’s School of Public Policy and is director of curriculum for ENFORM, a business sustainability forum for multi-nationals headquartered in the southeastern U.S. region (www.enform.info).